Bonanza PIT 2002 - Passport in Time

Main menu:

Previous Projects > States G-L

The Bonanza PIT Project

Salmon-Challis National Forest, Idaho, 2002

by Esther Morgan, FS Archaeologist

Modern field archaeology no longer involves just strings, trowels, picks, brushes, and shovels. We’ve gone high-tech! Starting with the discovery and recording of a site, down to the analysis of the last artifact and the publication of the report, there are devices that allow us to do the work faster, more thoroughly, and more precisely than ever before. But these devices are still just aids; they have not replaced the need for hands-on fieldwork. The modern crew member, however, has to have a considerable degree of technical sophistication. The objectives of the Bonanza PIT project were to introduce each volunteer to the technological side of modern archaeology, to collect significant data about this important mining camp, and to generally have a good time.

It was successful on all three accounts.

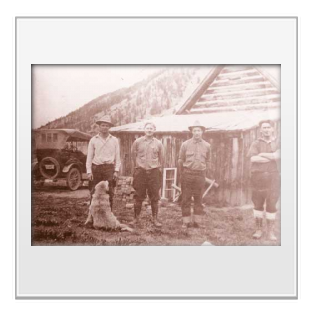

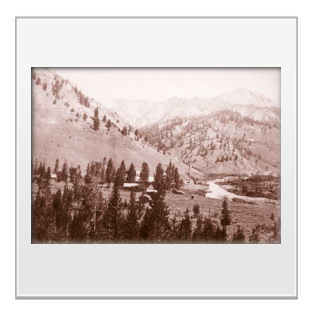

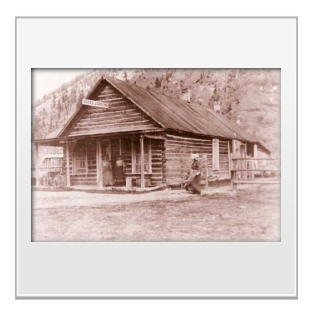

The Stanley Basin in central Idaho was the focus of intensive mining activity from the 1860s on. Bonanza, one of two major camps along the Yankee Fork River, was established in 1877. Following the pattern that characterized so many 19th-century mining camps, Bonanza went through boom-and-bust cycles, reaching a peak population of perhaps 1,500 around 1880. After that, the population declined, although a small resident population hung on until well into the 20th century. The site is now completely abandoned. A few of the original buildings remain in various stages of collapse.

Between July 8 and 12, 2002, a PIT crew consisting of 2 FS employees, 4 volunteer staff members, 20 volunteer crew members, an archaeological consultant, and 3 archaeology students from Boise State University (BSU) worked at the site. The entire staff and crew camped at a nearby FS campground for the duration of the project. Specific archaeological goals for the 2002 field season included defining the site’s extent and comparing its boundaries with historical-period documents and maps. We also hoped to determine whether the site had the potential to yield important information about late-19th- and early- 20th-century lifeways on the Yankee Fork. FS staff will use all the information collected to make informed decisions about the management and preservation of the site. And finally, we hoped to provide all volunteers with an introduction to the wide variety of technological applications that can be used in site recording.

To accomplish these ends, the crew was divided into four teams. The first of these was the on-site recording team or “artifact team.” This team recorded and flagged artifacts and features across the known extent of the site. A second team, the, “perimeter team,” was kept busy surveying the area outside the known boundaries of the site to confirm or refine its boundaries. A “building team” focused on the dozen or so partially standing and collapsed structures, recording as much architectural detail as possible. Lastly, there was the “instrument survey team” that used electronic survey instruments to record the features and artifacts identified by the other teams. Crew members were allowed to rotate between teams on a regular basis according to their comfort levels and personal interests.

Wherever practical, each of the operations involved applications of current technologies. These included digital photography, GPS, a total station survey instrument, and laptop computers. The data collected were managed with geographic information system (GIS) and computer-aided drafting software. Coordinating the use of technology was Tim Goddard, an archaeologist on temporary leave from Archaeological Consulting Services, Ltd., of Tempe, Arizona.

Prefield research yielded documents showing earlier road alignments, town plats, and mining claims. These were converted into digital data, and as information from the various sources accumulated, we were able to use the laptop computers on a nightly basis to compare the prefield information with the data we were collecting in the field. Each night, the map of the site became more detailed. By comparing the ever-evolving map with other surface information from sources such as aerial and historical photographs, we could identify those locations where additional data were needed and concentrate our efforts on precisely those areas.

For example, present-day hearsay and initial field reconnaissance suggested that a major portion of the business district had been destroyed when the river was dredged for gold between 1946 and 1952 and when the present road along the river was constructed in 1975. In particular, it appeared that the site of the Dodge Hotel, one of the most prominent buildings in the town, had been completely destroyed during road construction, and the Chinese neighborhood had been removed by the dredge. However, our nightly analysis of the mounting data suggested that this was not entirely true. A small knoll east of the road seemed to be on the back of the hotel lot, and the area between this knoll and the limits of the dredge work should have contained the remains of the Chinese neighborhood. The attention of the artifact crew was shifted to this area with gratifying results. The east side of the knoll contained a concentration of artifacts that would have been in keeping with an upscale 19th-century hotel, and the area below the knoll was rich in Chinese artifacts. The spatial, photographic, and artifactual data are still being analyzed, and conclusions are being refined. Rick Fell, one of the BSU students, is using GIS to create an electronic map that will allow the user to simply click on any feature and bring up data, sketches, and even photographs. Our conclusion at this point is that enough of the site remains to be considered historically significant for preservation efforts and for later research and interpretation. Further PIT projects at this fascinating site would be productive and are a real possibility.