Hope Valley Arborglph 2011 - Passport in Time

Main menu:

Previous Projects > States A-F

Hope Valley Arborglyph Survey

Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, California, 2011

By Sue Kovach Shuman, PIT volunteer

Searching for Basque Arborglyphs on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest

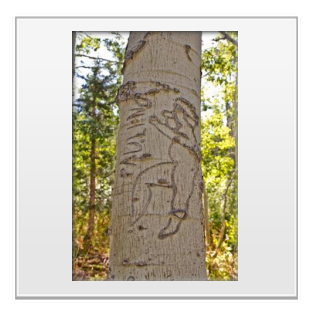

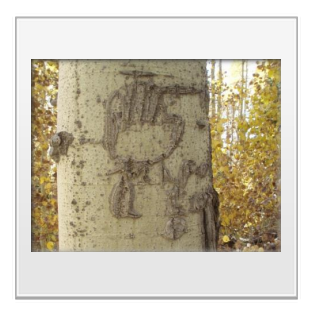

Their names were Alfonso, Jose, Manual, Antonio… They were lonely sheepherders, far from their Basque villages in Spain and France, who came to America for what they perceived as a chance for a better life. Away from family and friends for weeks or months at a time, they created their own forms of entertainment - such as carving trees. What they carved between the years 1870 and about 1970 can still be seen in aspen groves - figures of women, decorative elements, patriotic mantras, sometimes just their initials. The carvings tell stories about their lives.

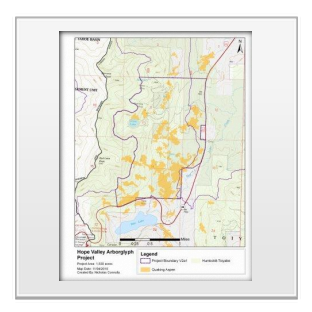

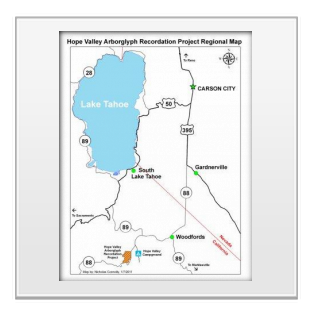

For five days this past September, a Forest Service geographer and a group of Passport in Time (PIT) volunteers set out on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest to preserve their legacy. Nicholas Connolly, based in Sparks, Nevada, has been documenting the carvings, known as arborglyphs, for some time for his Master's thesis in Geography at the University of Nevada, Reno. The region of the forest where they are found lies in both Nevada and California, on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The project, "Hope Valley Arborglyph Survey 2011," focused on two of these areas south and east of Lake Tahoe: Hope Valley and Horsethief Canyon.

Connolly was joined by four others from the Forest Service: archaeologists Alyce Branigan, Joe Garrotto, Mary Parrish and Sarah Kunnen. The volunteer portion of the team included Lauren Smyth, Jana Williams, Ruby Lowery, Nancy Nagel, Diane Wilson, Jim Blaes and Jim Goertzen. Together they scoured the forest for arborglyphs, and documented 157 panels on 152 trees, mostly in the canyon.

NAMES AND FACES ON TREES

NAMES AND FACES ON TREES

Connolly reports that he began his search for arborglyphs in August 2008 while doing an archaeological survey for the Carson Ranger District of the Humboldt-Toiyabe. "I was instantly drawn to the black carvings on the white aspen trees. The faces and names on the trees presented many questions and called for further research." After that survey was completed, he said he decided to continue looking for arborglyphs while pursuing a Master's degree in Geography at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Dr. Kate Berry, who serves as Connolly's advisor at the University, also participated in this PIT project, and in October brought her undergraduate class to the forest to practice field methods through documenting arborglyphs. In addition, a man who might be called the "Father of Arborglyphs," Dr. Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe, a historian at the University of Nevada and the author of "Speaking Through the Aspens: Basque Tree Carvings in California and Nevada," joined the group as a PIT volunteer and project advisor. Sporting a black beret, he walked with volunteers in the groves and explained how he deciphers messages on the trees. Some messages are clear, but time and weather have warped tree bark and altered the carvings. Connolly explained that Dr. Mallea-Olaetxe's extensive knowledge about Basque sheepherding helped him choose survey locations based on what had been seen previously. "He could answer any PIT volunteer question on the spot," Connolly said. "He was a huge asset because he provided everyone with an arborglyph education, without it feeling too much like a classroom."

Connolly believes there might be thousands of arborglyphs on the forest now, but there were likely many more in the past. "Unfortunately, we will never know what those arborglyphs said because they have been lost to time," he explained. "This is a critical time to be recording arborglyphs because of the time line. Arborglyphs were created by sheepherders between the 1870s and the 1970s. The average life span of an aspen is between 80 and 100 years." The earliest date recorded during the Hope Valley arborglyph project was 1908. "This is not to say that there were no sheepherders before 1908 in this area, but that the trees and the carvings have been lost."

Joe Garrotto, archaeologist for the National Forest's Carson Ranger District, explained why documenting the arborglyphs is so important: "The Basque men that carved their names in the trees and carved images important to their lives were some of the first settlers of this area. The carvings are disappearing as they are on living trees, and will eventually die and decay. By recording the carvings, this project has helped to preserve this unique part of our history."

Within the next five years, Connolly hypothesizes that at least three of the trees the PIT group recorded will be lost; within the next 10 years, two more will be gone; and within 15 years, 15 more. "Arborglyphs also are being lost elsewhere," he said. "They were also carved in forests in Nevada, California, Idaho, New Mexico and Oregon."

Arborglyphs are often difficult to find. In some areas of the Hope Valley Arborglyph Survey, trails were apparent, but many arborglyphs were found only after bush-whacking through underbrush in aspen groves. In some areas, fresh bear scat kept PIT participants literally on their toes! Each arborglyph was marked with tape, assigned a number and recorded - tree diameter, height from ground, location of panel, and other factors. Photographs were taken and sketches made. Forest Service archaeologist Alyce Branigan patiently instructed volunteers in the use of GPS techniques and coached them on reading maps of the area.

Some arborglyphs contained only the carver's initials or surname, and a date. Some have historic or cultural themes, like patriotic phrases, symbols, herders, or animals. Others contain swear words and sometimes (porno)graphic depictions of men, women or both, leaving little to the imagination.

Connolly told the group that he has many favorite arborglyphs, but especially likes one he dubbed the 'Paulino Figure Carving.' "I like the story that the carving tells. I also think the carvings with Alfonso L. (Aug 21, 1928), Antonio R. (Aug 5, 1919), and Frank A. (1952) all on the same tree are interesting….they seem to be paying respect to the previous sheepherder. They all know what it's like to be out there alone. Maybe knowing that the others where there before made them feel not as alone."

PIT volunteers Ruby Lowery and Nancy Nagel used their artistic talents to create rubbings of some of the arborglyphs. Lowery's mother, Mari Irueta, is quoted in Dr. Mallea-Olaetxe's book. Irueta was born in Nevada to immigrant parents who spoke different dialects.

AFTER WORK, EVENING ACTIVITIES

Some volunteers stayed in tents or RVs at the Forest Service's Hope Valley campground, a newly renovated site at about 7,300 feet above sea level, surrounded by lodgepole pines. Blaes caught fish for dinner one night in the nearby West Fork Carson River; Goertzen even went swimming there. Williams organized a potluck dinner and grilled chicken hash. Connolly provided the ingredients to make S'mores over the fire pit one night. For city and suburban dwellers (like me), the best thing about camping was the opportunity to see the stars shine so brightly in the sky every night - wow!

One evening, project participants drove to Gardnerville, Nevada, about half an hour away from Hope Valley campground, for a meal at J.T. Basque restaurant. The front room is a bar with dollar bills stuck to the ceiling. Heaping bowls of cabbage soup, oxtail stew, beans, salad and fries, all served family-style, disappeared quickly. Entrees included garlicky lamb chops and steaks, washed down with carafes of red table wine.

The project ended with a visit to Alpine County Museum in Markleeville, California, where museum staffers and volunteers baked pizzas in a traditional brick Basque oven for the group.

The PIT project is over, but Connolly's work is not done. Raw data is being entered into site forms and a written report will be sent to the California State Historic Preservation Office. A Forest Service database on the arborglyphs will help staffers to more easily manage the area's natural and cultural resources. Connolly explained the importance of that database thusly: "As an example, if there is a fire in the region of Horsethief and there are limited resources, firefighters can be instructed to try and protect the areas containing arborglyphs because we (Forest Service) know where they are."

By May 2012, Connolly hopes to have completed his thesis, based on the data collected by this year's PIT project.

[Author's note: If you're not used to the high altitudes of the region, a gradual ascent or a few days of acclimatization is advisable, as well as eating light, nutritious meals and drinking plenty of water. I flew from sea level on the East Coast to Reno and drove straight to the campground. The next day, I had a sudden headache, was short of breath and nauseated - symptoms that are part of altitude sickness. It occurs when you can't get enough oxygen from the air and is usually more severe if you smoke or suffer from heart and lung ailments. With rest, water, and a Forest Service-issue electrolytes drink, I recovered.]