Chippokes Plantation - Passport in Time

Main menu:

PIT Highlights > Headlines > 2009

Volunteers Dig In

George Washington-Jefferson National Forest, Virginia, 2009

by Diane Tennant, The Virginian-Pilot

Wannabe Archaeologists join a volunteer program that the pros say helps them accomplish more than if they relied on government budgets and their own hands.

Chippokes Plantation State Park

Richard Brunelle is more or less like a famous fictional character, and you can take your pick of which one – Indiana Jones or Little Miss Muffet.

He sublimely ignored the six daddy longlegs capering about the red flag that marked the dig.

In fact, he sat down beside them on a fallen log to do paperwork, which is never in short supply at an archaeological site.

“This is Level 1, and it’s going to be very, very thin – between one- and two-tenths of a foot. An inch or two,” he said, and measured it with an engineer’s ruler to be certain and wrote it down.

Brunelle is a retired medical imaging serviceman. In the woods next to him, digging another hole, were a high school junior and a physical therapist. On the far side of the park, in what some might consider their normal roles, a lawyer and a news reporter from Hagerstown, Md., also were digging up dirt.

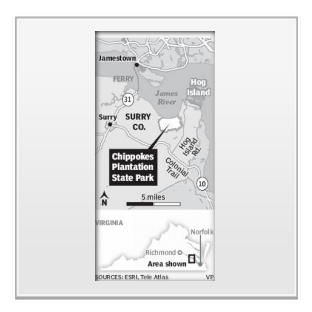

Across the park in Surry County, 50 volunteers from two countries, several states and all walks of life were shoveling and scraping and sifting in a public archaeology program called Passport in Time.

They get to indulge their inner Jones, and the professional archaeologists supervising them get to accomplish more than would ever be possible if they had to rely on federal or state budgets and their own hands.

It’s a perfect situation, if you don’t mind spiders.

Mike Barber does not mind spiders or, in the case of the daddy longlegs, their relatives. He does not mind the chill in the air either, and he strolled from site to site wearing shorts while everyone else wore coats.

“What we’re trying to do is just get the concept of archaeology before the public,” said Barber, who is Virginia’s state archaeologist. “These folks really, really want to be here, and they really want to do archaeology.”

At Chippokes, the volunteers were looking for evidence of three cultures that used the bluffs above the James River over hundreds of years. Brunelle and five other groups were looking for evidence of Native Americans who were there from as early as 500 B.C. and of the European colonists of the 1600s. On the other side of the park, near the slave quarters built around 1814, another group of volunteers was gathering artifacts from the plantation era.

“It’s an amazing place,” Barber said. “What we have here is the concept of ‘creolization.’ The Colonists got a lot of influence from the Native Americans here and also the Africans who came over and had an influence on the culture as well.”

Creolization is echoed by Passport in Time, or PIT, which also brings together disparate individuals, and melds them into one.

“I work for McGraw-Hill,” said Kelly Ball of Columbus, Ohio, as she shoveled in the woods. “This is my second vacation doing this. Is that flint?”

“You know, this looks like it has a serrated edge on it,” said Belinda Urquiza, who usually works on Capitol Hill, as she scrubbed the small object with a toothbrush.

She took it to the site supervisor and asked, “What do you think? A base? A scraper?” The supervisor said, “This is a gun flint.”

“Oh, great,” Urquiza said. “I’ve never had a gun flint before. So we have historic and prehistoric.”

And the supervisor said, “A little bit of everything here.”

PIT is run by the U.S. Forest Service, which lists on its Web site, www. passportintime.com, archaeology projects that are looking for volunteers. The program is extremely popular, despite the facts that participants usually pay their own transportation, may have to bring their own tents and buy their own food, and spend most of their time in hard physical labor.

One hundred applications were received for the sevenday Chippokes dig; only 50 could be accepted.

Melissa Paulson of southwest Virginia arrived halfway through the week with her daughter, Sara Stallings, a high school junior who wants to become an archaeologist. The two knelt on thin rubber pads and enthusiastically scraped away thin layers of soil with trowels, pausing often to clip roots that got in their way. Over the summer, the two dug at Camp Misery, a Civil War site near Fredericksburg.

“It’s really cool coming out because you don’t have to know a thing,” Paulson said. “You get such a feel for being in the spot where history happened.”

At Chippokes, the Forest Service joined forces with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, where Barber works, and the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, which runs the state park. PIT participants had a choice of camping in the park or staying off-site – some stayed in Williamsburg hotels and took the Jamestown-Scotland Ferry back and forth.

Peter Bon, a retiree from Delaware, said he joined PIT in 1999 and now works with Barber every year. As buckets of dirt were dumped onto a quarter-inch-mesh screen, he shook it vigorously to separate the artifacts from the soil.

“Hey, guys, nice going,” he called. “You got a piece of curved glass here.”

“Which means … ?” a digger said.

“It wasn’t a window pane.”

The soil had been dug from a pit behind what might have been the outdoor kitchen of the plantation’s original house. Every bucketful turned up treasures: shards of pottery and porcelain, some with the maker’s mark intact; bits of glass; pieces of bone.

A second pit had glass bottles protruding from the bottom and sides.

“That’s a lot of domestic debris in one hole,” Barber said. “This is definitely cool.”

Brunelle dug and screened by himself in the woods, testing a small hole to see whether enough artifacts turned up to warrant a larger pit. He found a small flake of quartzite chipped from a projectile point by an Indian craftsman hundreds of years ago.

A few feet away, the gun flint turned up. During the week diggers also had found smoking pipes, bottles and lead shot.

“It’s probably a heavy concentration of men who were smoking, drinking and shooting things,” Barber said. Mike Madden, a Forest Service archaeologist, added: “This site is kind of weird. We’re not sure whether it’s a mustering site for hunts.”

In the woods nearby, Brunelle found another flake of quartzite, which he sealed in a plastic bag and labeled. He sat down on the log to fill out paperwork again, beside the daddy longlegs.

Just like those famous fictional characters. Give or take the paperwork.